Francesco Rugeri

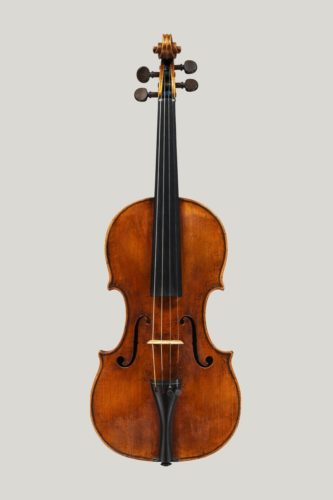

Violin made by Francesco Rugeri in 1670 in Cremona. Ragnhild Hemsing plays on this instrument.

There are few finer examples of Francesco Rugeri’s work as a violinmaker than this instrument of the Dextra Musica collection.

His extraordinary output, which all seems to stem from a comparatively short period between 1670 and his death in 1695, provides us with a wealth of finely crafted and beautifully toned instruments. At the beginning of this period, Francesco was already 50 years old. The assistance of his four sons, Giovanni Battista, Giacinto, Vincenzo and Carlo cannot be underestimated, but it is virtually impossible to disentangle their various individual contributions. Only Vincenzo carried on in his profession long enough after his father’s death to leave an identifiable body of work, from which we might be able to perceive his hand in earlier instruments bearing his father?s label. Like Antonio Stradivari, Francesco Rugeri lived long, and rather overshadowed the work of his own sons.

Other parallels with Stradivari exist. He emerged as a maker at about he same time; Stradivari’s first work is dated 1666, Rugeri’s are from 1670, yet Rugeri was Stradivari?s senior by 24 years. Both men are linked traditionally to the Amati workshop, although neither left any documentary evidence of the connection. But both are connected by a peculiarity of technique. All previous Cremonese makers left a small hole, often plugged with a wooden peg, in the middle of the interior of the back. This is assuredly an integral part of the constructional technique developed by the Amatis and handed on to their direct pupils. Neither Rugeri nor Stradivari instruments exhibit this easily overlooked but important feature.

The comparison between Rugeri and Stradivari is otherwise a little unfair. Rugeri was a fine craftsman in the exacting Cremonese tradition; Stradivari was a genius. Rugeri remained loyal to the Amati forms and patterns throughout his working life, but by the time of Francesco’s death in 1695, Stradivari had totally transformed the principles of violinmaking and was just embarking on his greatest period of production. It is interesting to observe Stradivari’s influence on the violins made by Vincenzo Rugeri, which show a flatter, more potent arching than his father’s highly built, curvaceous forms.

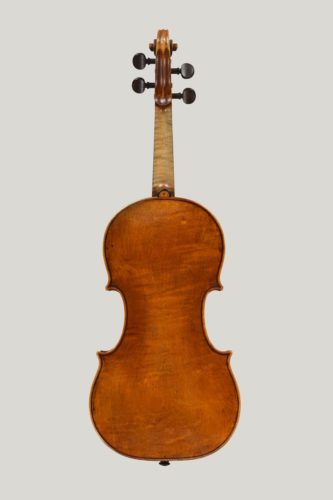

This violin utilises Nicolò Amati’s ‘grand pattern’, a widened version of earlier forms. Rugeri has given it a particularly full arching, with a flattened area along the centre part of the front, and only a light recurve at the edges. Rugeri’s purfling is neatly inlaid, but lacks the extended mitres at the corner joints that are a feature of Amati’s work. Rugeri is unique amongst Cremonese makers in using maple for the white core of the inlay, a small but again significant variation from the Amati style. The scroll is also very representative of Francesco’s work. It possesses a slight ovality in the volute, with a broad first turn which is left flat, the undercutting of the spiral increasing dramatically as it approaches the eye. All the surfaces are finely finished, apparently cut cleanly with edge tools rather than polished with abrasives.

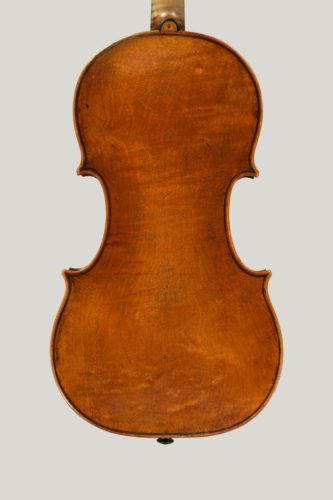

The wood choice is typical of Rugeri, with a fine single piece of subtly figured slab-sawn maple providing the back. The well-flamed ribs are cut more conventionally on the quarter. The front is of the usual fine-grained alpine spruce, quarter-cut and jointed in the centre. The instrument still bears a remarkably well-preserved coating of fine orange-brown varnish, illuminated by a rich gold-tinted ground.

Ragnhild Hemsing

Ragnhild Hemsing’s (b. 1988) unique upbringing close to the folk music traditions of Norway enables her to present modern and individual classical performances that evoke the style of folk traditions. (Photo by: Thor Østbye)